Anyone who has kept a backyard flock eventually faces a dilemma. As hens age their egg laying slows. Eventually it nearly stops. There’s a point where the girls eat expensive feed yet hardly lay an egg. How does a flock owner decide when to get rid of aging hens and what to do with them?

A Laying Scenario

A young pullet starts laying when she is 18 to 24 weeks old. If she’s of a productive breed she’ll soon lay like fury. It takes about 26 hours for an egg to form, so every once in a while, she’ll take a day off, but a flock of six young hens should average five eggs a day. Sometimes six eggs will be in the nest and other days only four. The flock should average about 80% production that first lay cycle.

Hens lay for a year or a little longer and then take a vacation, called the molt. They’ll lose their old worn feathers, regrow new ones, beef up the body, and start the second laying cycle after a six to eight week laying pause.

They’ll follow the lay/molt cycle throughout their lives. After each molt hens lays fewer eggs, so that is a problem for a small flock owner. The 80% lay rate of a young flock will usually drop to about 70% in the second cycle. This cycle falls at least another 10% a year in subsequent cycles.

An individual hen can lay for ten years but by the time the flock is four or five years old, egg production is so low it hardly justifies the feed cost. To keep production high flock owners replace their aging hens every two or three years.

How To Tell if A Hen’s Not Laying

Telling whether a hen is consistently laying is an important skill. Although few older birds lay well, even an occasional younger bird will consume feed yet lay few eggs. Here are ways to identify a non-layer:

- Age: Keep track of how old your hens are. Few hens lay well after they pass their fourth or fifth hatch day.

- Appearance: Productive hens look great early in their egg laying cycle but start looking rough as months go by. Their once yellow beaks and legs lighten and feathers become worn and a bit ragged. A hen that looks like she stepped out of a spa is putting her energy into appearance not eggs. She’s a stew candidate.

- Feeling Pelvic bones: Laying hens have wide spaces between their pelvic bones, but these bones on non-layers are close together.

What To Do with Non-Laying Hens

Mentor Hen: Older hens have value. Keeping a veteran hen or two with the new layers helps them pass their wisdom down to the younger generation. It’s perfectly fine to keep old, rarely laying hens, but they are more pets than food producers.

Stew: People get attached to their hens. They can’t bear to convert them to stew, and many town ordinances forbid slaughtering chickens. However, the meat of older hens is tough but tasty. When stewed with onions, potatoes, carrots, and spices they make delicious fare.

YouTube Videos show how to butcher chickens. It is the ultimate DIY project. However, if slaughtering isn’t allowed, or the flock owner just won’t, or can’t, do it, turn to social media.

Give them Away: Many people are happy to take old hens. Ads on social media offering free birds will likely bring takers. A few may keep them but most will transform them into stew. They’ll slaughter them out of the sight of the previous owner.

Records Are Important

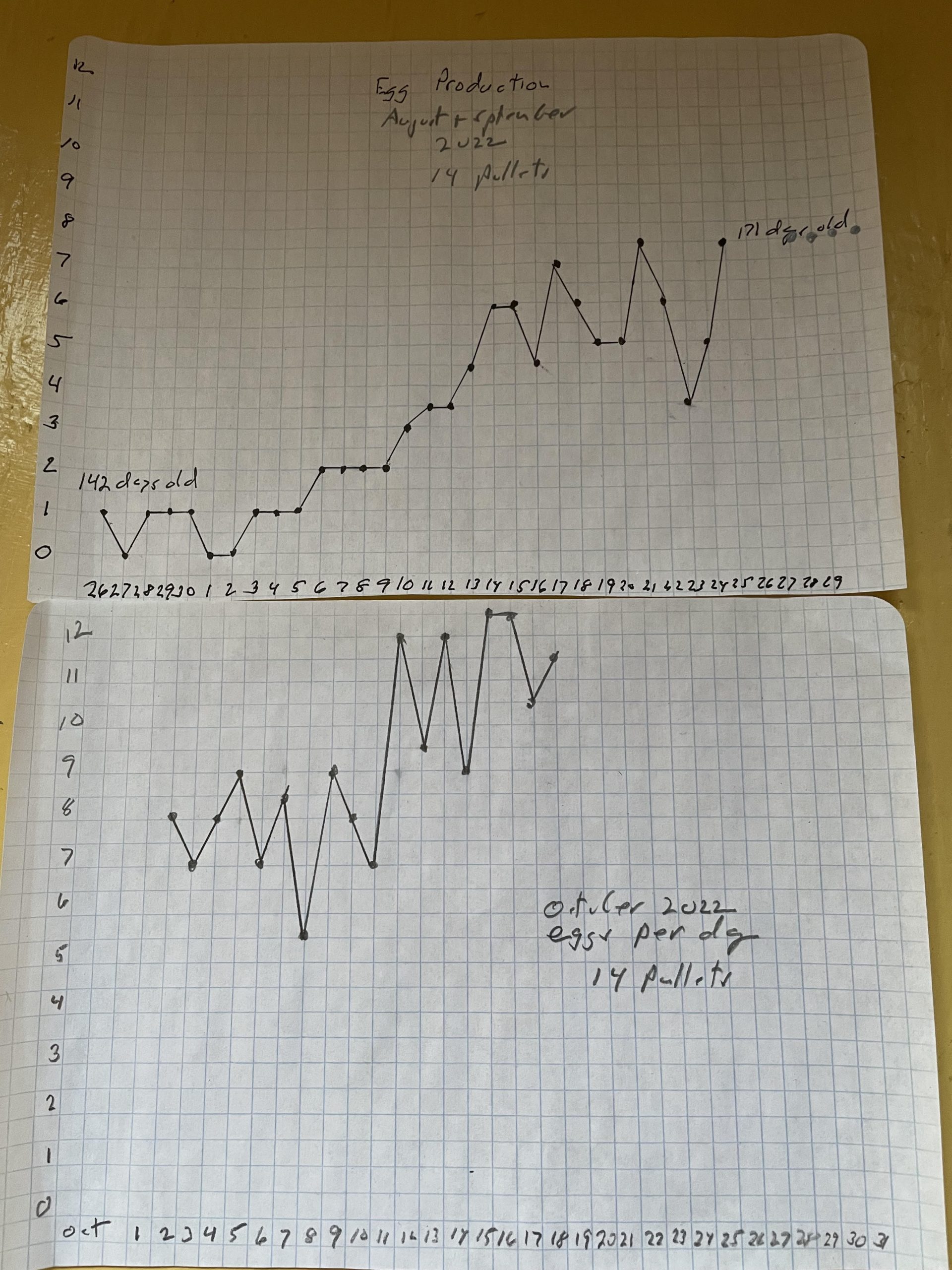

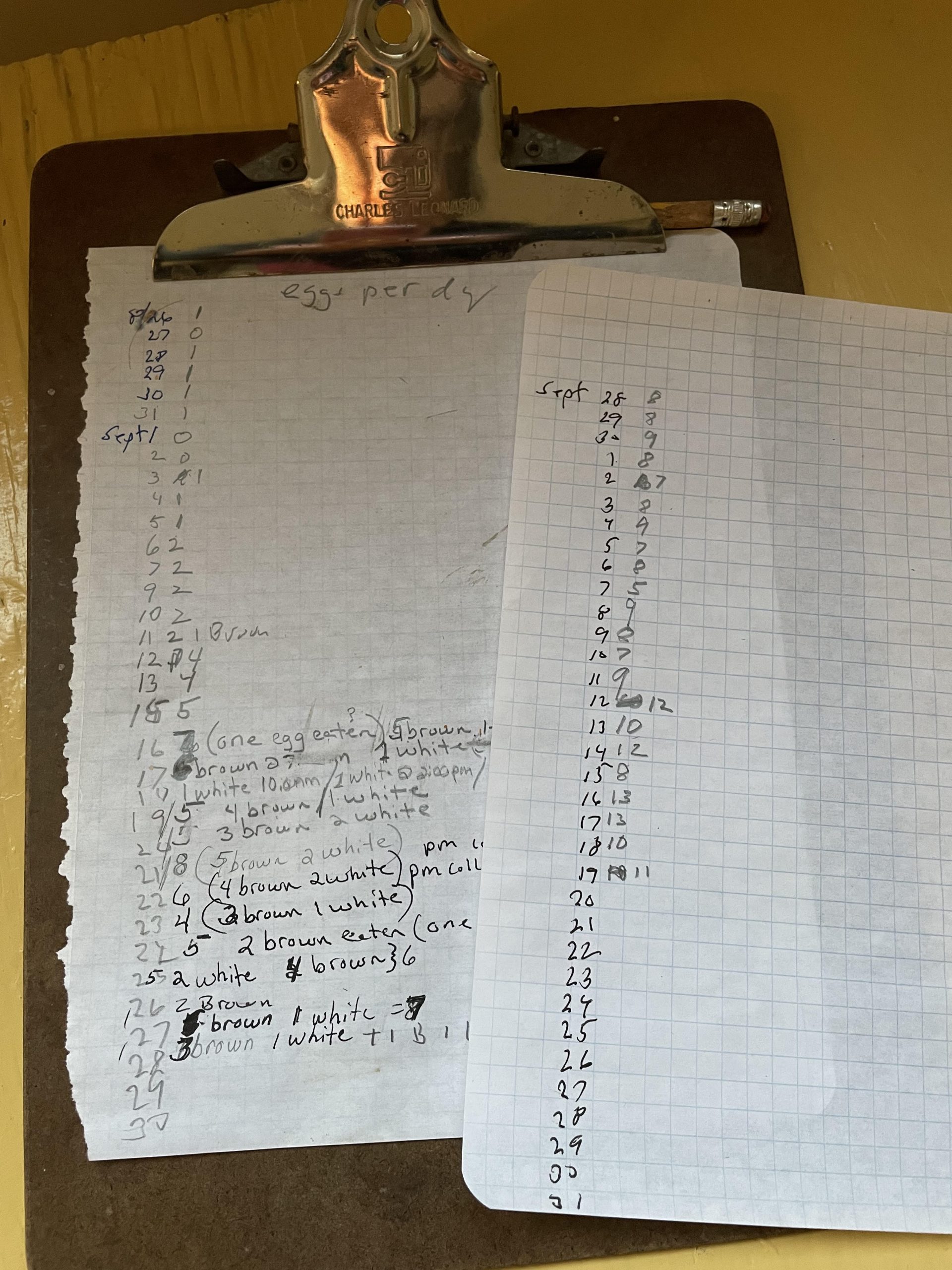

Keeping egg production records is important and a great way for children to learn basic data collection, graphing, and interpretation. Keeping a clipboard in the coop and recording daily egg production helps monitor efficiency. The information can then be transferred to the computer to enhance typing and analysis abilities. Yet another set of valuable modern-day skills. Graphing data shows the ebb and flow of egg laying.